Healthy Aging: Embracing Quality Life Years

The quest for healthy aging transcends the mere desire to extend life; it’s about enriching those additional years with vibrant health. The report underscores the significance of nurturing heart health, managing weight effectively, and maintaining hormonal balance.

For heart health, it champions the consumption of omega-3 fatty acid-rich foods like salmon, flaxseeds, and walnuts. The report also recommends whole grains and leafy greens to regulate blood pressure.

For heart health, it champions the consumption of omega-3 fatty acid-rich foods like salmon, flaxseeds, and walnuts. The report also recommends whole grains and leafy greens to regulate blood pressure.

Weight management strategies include a balanced diet of lean proteins, complex carbohydrates, and healthy fats, highlighting foods such as quinoa, lean chicken, avocados, and legumes to preserve muscle mass and metabolism.

To support hormone health, incorporating phytoestrogen-rich foods like soy products, along with antioxidants from berries and nuts, is advised for hormonal balance and endocrine system support.

The Evolution of Clean Labels: Seeking Simplicity & Transparency

Today’s consumers crave simplicity and transparency in their food choices, a shift evident in the rise of minimally processed foods. This trend towards clean labels reflects a growing skepticism towards overly processed foods and complex ingredients. The advice here is clear: seek out products with short lists of whole, recognizable ingredients (click here for what we mean by this!), and exercise caution around items with artificial preservatives, colors, and flavors.

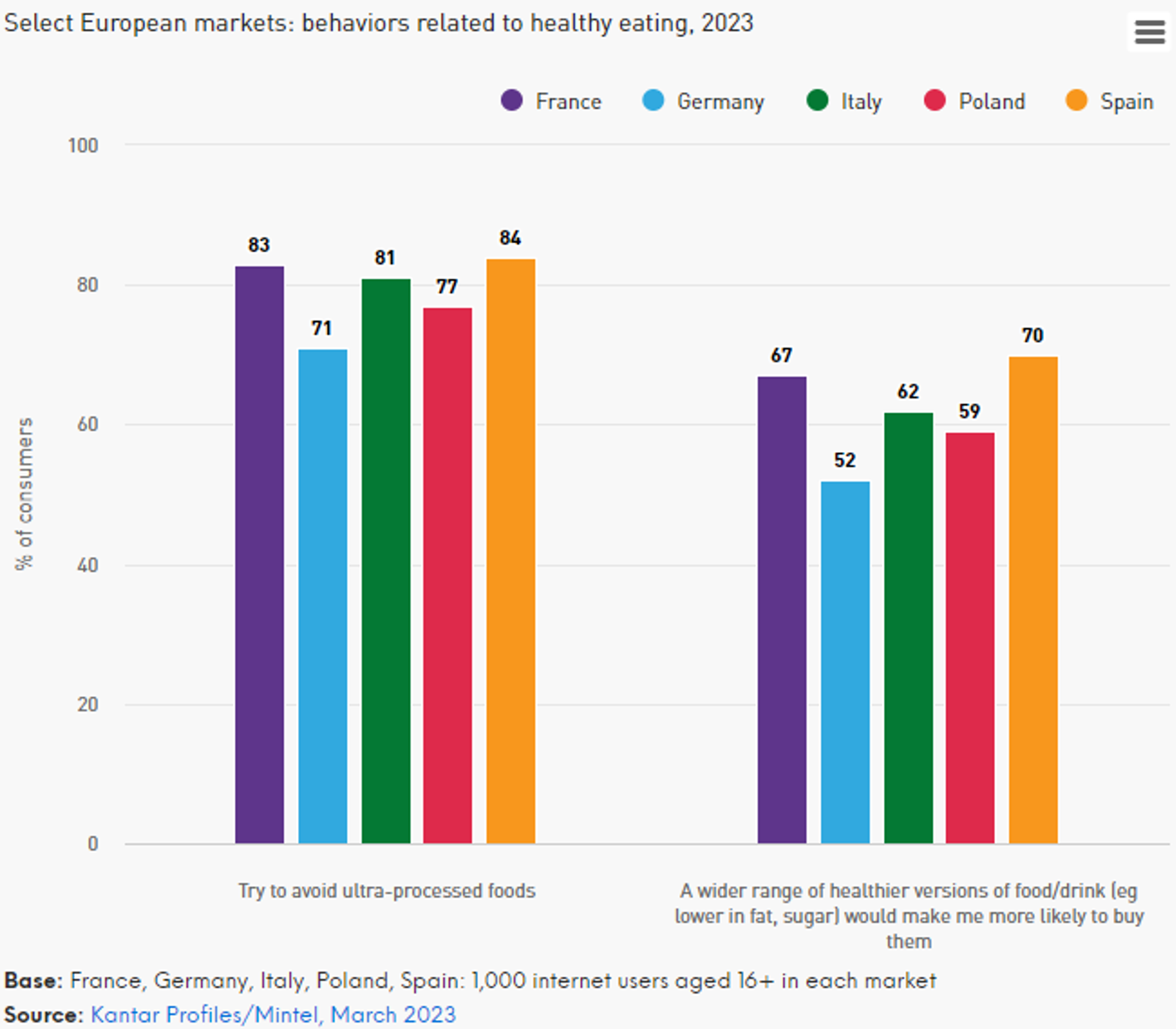

It is not that those ingredients are bad for you, but you want to look for foods that have more healthy nutritious ingredients that add value to your body. The report also points to a burgeoning interest in traditional and artisanal food-making processes, which promise less processed and more nutrient-dense food options. Our tip: Shop the perimeter of the store and avoid added sugars in processed food choices! As Mintel reports:

It is not that those ingredients are bad for you, but you want to look for foods that have more healthy nutritious ingredients that add value to your body. The report also points to a burgeoning interest in traditional and artisanal food-making processes, which promise less processed and more nutrient-dense food options. Our tip: Shop the perimeter of the store and avoid added sugars in processed food choices! As Mintel reports:

“Go back to the basics to help consumers age and live well by keeping hearts healthy, supporting weight management and improving muscle mass.”

Purposeful Processing: Marrying Innovation with Nutrition

Purposeful processing emerges as a strategic approach for brands to align products with health and wellness objectives without compromising on flavor or quality.

Techniques like fermentation, which boosts gut health, and cold-pressing, preserving nutritional integrity, are highlighted.

Consumers are encouraged to explore products leveraging these innovations, as they tend to offer superior nutritional profiles.

Adding in more plants to your diet, (but don’t forget the benefits of dairy and meat in moderation), the report advises looking for products that highlight the natural benefits and flavors of plantsover those laden with additives to mimic animal products.

When looking for animal products, seek quality fish, meat and poultry.

Aging Populations: Forward-Thinking Nutrition

An aging population necessitates a proactive stance on nutrition. For the aging demographic, it calls for nutritious, accessible, and easy-to-prepare food options to meet older adults’ unique needs. Suggestions include focusing on foods that support cognitive health, bone density, and hydration, such as fatty fish, calcium and vitamin D-fortified dairy, and easily consumable fruits like berries and melons.

“According to the United Nations, one in six people (1.4 billion people) will be aged 60 or older by 2030.

While seniors are a diverse group with diverse needs, protein and hydration are two important areas to focus innovation on.”

Key Takeaways for Consumers: Navigating the Nutrition and Wellness Landscape

- Prioritize Holistic Health: Embrace a diverse diet that bolsters heart, weight, and hormone health with a focus on nutrient-dense foods. Moderation and variation is key!

- Embrace Transparency: Opt for products with straightforward labelling (see our label guide here!) and appreciate the value of traditional food processing methods.

- Explore Innovation: Remain open to trying products that incorporate purposeful processing technologies to boost nutritional value without sacrificing taste. Embrace new technologies in the food space, they may just benefit you from a nutrition standpoint and a sustainability standpoint!

This analysis of the Mintel report provides an educational guide for consumers aiming to make informed decisions about their health and nutrition amidst changing global food trends. The key is to remain curious, adaptable, and informed, paving the way for a healthier, more sustainable lifestyle. But how do we know where to get our nutrition research?

Other Considerations

In addition to the insights provided, Mintel mentions that it’s crucial to consider the impact of digital technology and social media on consumer health choices and perceptions.

The rise of health and wellness apps, online communities, and influencer-led health trends significantly influence dietary decisions, often blurring the lines between scientifically backed advice and anecdotal evidence. Understanding how to critically evaluate these sources of information and discern credible advice from mere fads is essential for consumers aiming to make informed health decisions. [HP1]

Furthermore, the role of mental health in overall wellness, emphasizing the importance of a balanced approach that nurtures both the mind and body, remains a critical area for exploration. The Mintel report focuses on the physical aspects of health, but the psychological impacts of diet, including how food choices can affect our mood and stress levels, are equally crucial. Incorporating foods known to support mental health, such as those rich in omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, and probiotics, can be another actionable step for consumers.

To avoid falling for societal misconceptions about health and nutrition, consumers can take several proactive steps:

- Critical Evaluation: Learn to critically evaluate health and nutrition information, checking the credibility of sources and the evidence behind claims. Are studies peer reviewed? Is the website selling their product which supports their analysis? Who is funding the study? Does it come from a reputable university or research engine? Is it an EDU or ORG website? This skepticism can help navigate through marketing hype and focus on scientifically backed advice.

- Personalization: Recognize that dietary needs are highly individual. What works for one person may not work for another due to differences in metabolism, lifestyle, and health conditions. Consulting with healthcare providers or dietitians can help tailor dietary choices to individual needs.

- Long-term Perspective: Adopt a long-term perspective on health and nutrition, focusing on sustainable changes rather than quick fixes (aka no fad dieting!). Slow and steady often wins the race when it comes to lasting health improvements.

By adopting these practices, consumers can navigate the forest of nutrition and wellness with confidence, making informed decisions that support their health and well-being in a balanced and sustainable way.